Usually my If you like Blyton posts are on modern-ish authors you might not have heard of, mixed with a few older things that again, you may not have read. This time, though, I fear I may be teaching your grandmother to suck eggs. You’ve probably read The Secret Garden, and if not, you’ve at least seen one of the films and are aware of the plot.

So why am I still going ahead with a review? Not because I’m desperate to find something to write about – though that’s a good a reason as any – rather because I just loved it so much.

A familiar story

I had never read The Secret Garden until a few weeks ago when I listened to an audiobook version. And yet, having seen the film – the 1993 one with Dame Maggie Smith as Mrs Medlock – I felt like I was reading an old favourite. I suppose that’s more testament to the faithfulness of the film adaptation than the writing, but never mind.

In case you aren’t familiar with the story of The Secret Garden, here is a summary.

Mary Lennox is a ten year old girl living in India when her parents die suddenly of cholera. She has never been loved by her parents but she has been spoiled by the servants and so is a cross, rude, demanding little girl. She is sent to England after the death of her parents and has to adapt to living in the lonely Misselthwaite Manor in the middle of the Yorkshire Moors. Her only company are her maid Martha, the crusty old gardener Ben Weatherstaff, and a little robin redbreast who flies around the garden, though soon she gets to know Martha’s brother Dickon, and discovers another young inhabitant of the Manor who’s mere existence has been kept a secret from her. She also, after some searching, discovers the Secret Garden of the title, and with Dickon’s help she works on the garden to try to restore it.

One of Blyton’s inspirations?

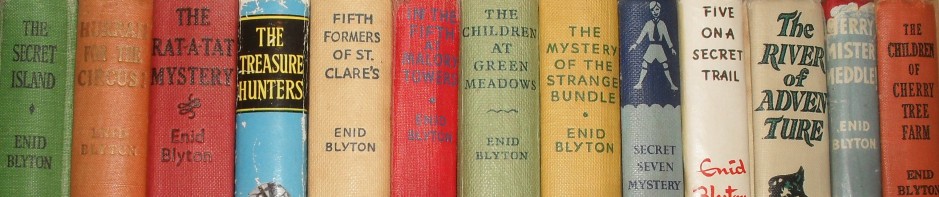

The Secret Garden was published in 1911, when Enid Blyton was 14. She might have felt too old for a children’s book at that age (though interestingly the book was marketed at adults and children when it came out), but she may well have become familiar with the plot even if she hadn’t read the book.

There is a great deal of gardening in the book, as Mary learns the joy of watching plants come to life in the spring, and she learns from Dickon how to prune rose bushes and how to tell if a bush or tree still has life in it. We know Blyton was an avid gardener and how she loved nature, inspired by her father, and she wrote many books (both fiction and no-fiction, and some a mix of both) about plants and nature.

Dickon is very much like Philip Mannering, he has a way with animals and has pockets full of squirrels, a tame crow who follows him everywhere, a fox cub he has raised, he even has a wild moor pony who he has tamed.

The discovering of Colin – the boy secreted away at the Manor – reminded me of the discovery of Kit in The Boy Next Door. In both cases the child/children discover a boy’s existence even when the adults deny such a boy exists. The reasons they are hidden, however, are quite different.

Having been scanning through The Mountain of Adventure for our latest fan fiction, I also noted that the entrance to the mountain; behind a curtain of ivy and brambles, is much like the entrance to the garden; hidden behind a curtain of ivy. Both blow away from their entrances at just the right moment to reveal their secrets to the child or children.

None of these elements are unique to Blyton or Burnett, if you took the time you could probably come up with dozens of stories with ivy curtain and boys being kept hidden, or boys who charm the wildlife (Wilfrid of Five Have a Mystery to Solve is another), but probably not all at the same time. I just found the parallels interesting.

The moral of the story?

There is a strong set of morals underpinning the story – and by morals I don’t mean preachy do-gooder morals. Saying that, though I find all the morals seem more like threads of the same moral, all intertwined.

I think primarily it is about the power of positive thinking. Mary arrives as Misselthwaite determined to hate everything, and yet as time goes on she starts to see it’s not as bad as she thought. Then when she makes up her mind to enjoy herself, she really does. Then Colin has always believed himself to be a cripple (the book’s words, not mine), and so has lived the life of a feeble invalid. After he meets Mary he decides that he is going to like getting up and going out, and so he does. He also decides he is going to walk even though he had always believed he couldn’t, and so he walks.

Of course positive thinking alone can’t solve a problem but it can help, conversely negative thoughts can make it harder to achieve something. I suspect that there is a religious undertone to the message here, as they almost form their own church to pray to the magic that they believe flows through the garden, bringing the flowers to bloom and Colin’s legs to work. However it is fairly discreet as Christ, God and so on are never mentioned, just magic and prayer and the sorts of things that are mentioned in religion.

There is something very Blytonian about the growth and development of Mary and Colin – how many stories has Blyton written about a spoiled or lazy child who later reforms their behaviour? Elizabeth Allen and the O’Sullivan Twins come to mind, but there are dozens of short stories with similar themes. Being short stories they don’t delve into the same depths of character development as we see in The Secret Garden, but the idea’s still there.

A few darker elements

There are several tragic and even quite dark elements in the book.

The sudden death of Mrs Craven in an accident in her garden, and her husband’s subsequent emotional abandonment of baby Colin due to his likeness to his mother. Colin, who is hidden away in his room, never spoken of outside the Manor, his existence actively denied.

Mary looks at the portrait of Mrs Craven, which Colin normally keeps covered. Illustration by Charles Robinson from the first edition.

The doctor who stands to inherit Misselthwaite Manor when Mr Craven and Colin dies, and for a long time has encouraged Colin to believe in his hopeless condition. Colin frequently says he believes he cannot live.

And some problematic scenes for modern readers

In general I don’t believe in banning books or butchering them to fit modern attitudes, but it can be helpful to know what to expect in a book before you read it, particularly if you are reading it to children. That way you can decide how you are going to discuss the racism, sexism, or other attitudes which are unacceptable today.

There is some colonial imperialism particularly in the early chapters – something that would surely be edited out if Blyton had written it. Mary says of her Indian servants They are not people.

The native servants she had been used to in India… were obsequious and servile and did not presume to talk to their masters as if they were their equals… Indian servants were commanded to do things, not asked. It was not the custom to say “please” and “thank you” and Mary had always slapped her Ayah in the face when she was angry.

Martha at first assumed that being from India that Mary would be black:

I dare say it’s because there’s such a lot o’ blacks there instead o’ respectable white people. When I heard you was comin’ from India I thought you was a black too.

However Martha also says she has nothing against the blacks, because she has read they are very religious – religious but not respectable apparently.

I don’t know what Frances Hodgson Burnett’s thoughts were on people from India. Was she merely putting words into a rich spoilt white girl’s mouth, and a poor uneducated servant’s mouth or did she really think that people from India were unequal to whites, and not people? I don’t know. The characters are certainly speaking from their time and say far worse things than I’ve ever seen in any Enid Blyton book. Both the quoted bits made me take a sudden intake of breath, and think how offensive those remarks are today.

There is also the expected classism, with the servants firmly knowing ‘their place’, though Mary begins to treat Martha as more or less an equal, and she never considers Dickon as anything less than an equal, in fact she is in awe of him.

What surprised me was that Mrs Sowerby (Martha and Dickon’s mother) provides food for the children while in the garden. Mrs Sowerby has 14 children, Martha being the eldest, so there are 13 at home. They are always hungry – this is made clear several times in the book with references to their never being enough to eat, the children eating the moor grass as if they were ponies and so on. And yet Mrs Sowerby provides food because Mary and Colin are so hungry from their exertions – hungry because they’ve deliberately undereaten meals served in the Manor as to not draw undue attention to Colin’s recovery which they are keeping a secret.

I really loved this book. I sometimes don’t enjoy books as old as this because the language can be a pain to unpick, many authors of the early 1900s and earlier were fond of dramatic lengthy sentences which in the end didn’t say very much at all (I’m looking at you, Charlotte Brontë). But this is very readable – or well, listenable, as it was an audio version I had.

Despite knowing the vast majority of the story from the film (which I now realise was incredibly faithful, other than leaving out the motivations of the doctor and some of the magic prayer meetings) I found myself hanging on every word. The unwelcoming manor, the wild and lonely moors and the abandoned garden really come to life in the book.

As with The Indian in the Cupboard I don’t feel like I’ve done this book justice with the review. I can’t express the feelings this book evokes with its various mysteries and secrets. But haven’t we all wanted to find a key, buried in the flower beds, and a door that hasn’t been opened in ten years with an overgrown garden behind it? I know I always have.

I have always had fond memories of the Secret Garden, although it’s been decades since I’ve read it (My mom actually read it to me, so that shows we’re talking probably 40 years ago) I didn’t know there was a movie in 1993-I remember a version from TV in the late ’80s (I don’t know if that is when it came out, or if that is just when it aired) My mom videotaped it back then, and funny enough, she was watching it not too long ago (during COVID, my mother has dusted off a lot of old VHS tapes to rewatch) If you like, I can find out the exact version I am talking about

LikeLike

Probably this one? https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0093935/. There’s a couple other adaptations but much earlier. I’ve not seen any of them, or the one that came out last year but I’d like to.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Maybe. Is there a clip of it I can watch? I don’t know from the cast list. Either way, it’s an interesting book. In my children’s book readings, I am currently rereading the Trixie Belden series. I don’t really think they are much like Blyton (but then again, neither are the Bobbsey Twins mysteries really), but I like them a lot. To be honest, while I like the Famous Five, and the two boarding school series, I am not as much into Blyton as I am other child mystery series (but definitely not the Hardy Boys or Nancy Drew)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hey Fiona, well, this shows exactly how much of it I remember-it was A Little Princess I was thinking of, not The Secret Garden (my mother recorded both as well as read them both to me) Sorry about the confusion though!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You wrote rather a nice review of the book. It may surprise you, but many on-line reviews don’t seem to think it worthwhile to give reasons for liking or disliking a book (or a tv show or movie) — they just give a slightly odd review, odd in that it’s completely unbalanced: they just say they liked it, taking far too long to do so, and never get around to saying why.

I think you perhaps didn’t emphasise enough at the outset that this was an audio book. A taped book is not really a novel, it’s rather more akin to a drama. With a printed book — even an electronic book – you are reading it. Obviously! You can go back, if a sentence doesn’t make sense. And you can pause and think about what the author is saying.

A taped book is more like a tv show or radio show: you’re much more in the hands of the performer. And a good audio book is a performance. An actor will try hard to make it so. Hence it can have something of the sense of drama about it, in that it can convey emotion in a way that is much more intense than the printed page can do.

You gave a good summary of the novel, but you didn’t try to give any impression of the actor who was performing it. You really treated it as if it was a book in your hands, not a tape. This is a bit inexplicable, because you were obviously moved by the emotions the story conjured up for you. but it seemed that this was an effect of the dramatic presentation of the story, yet you skated over the fact that it was presented as a drama. In the end, I think you reacted so strongly to the story because your original memories were from seeing it on television, as a drama; and now you were having that same experience again, only very slightly modified, as the tape is something akin to a radio play. You’ve never gotten within touching distance of the book which both were based on, so your whole experience of the story is through drama,

It’s not difficult to understand how drama can produce an emotional response. But I think perhaps you are still thinking of this story as a book in the printed sense, even though you’ve never read it. An adaptation for broadcasting is a very different thing. And now you’re trying to write down on paper – well, almost – a review of a play (if you think of it as a radio play on tape); but you thought you were writing a review of a book! It’s still a nice review, but it wasn’t really a book you were reviewing…

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think I have to disagree with you on just about every single point.

I clearly stated at the beginning that I had listened to an audiobook, and beyond that the format was irrelevant.

I was reviewing the story – the plot, the characters and so on, and recommending it to my readers based on that. Being out of copyright there are dozens of audiobook versions available and so there would be little point in my recommending the audiobook I listened to as there are dozens of other narrators out there. The narrator I had was good; she did a convincing range of accents and made the characters distinct from each other. I listened on a faster speed however as I find most narrators read too slowly for my liking.

If the narrator had been terrible it would have affected my enjoyment but I have listened to many books which I have also read in print and I don’t consider any audiobook a “drama” or anything less than a book in its own right. The voices may be provided for you but you still have to visualise the characters and locations etc. Incidentally you can rewind and pause an audiobook with only slightly more effort than it takes to stop reading or reread a printed book, and often I do do that. In short, my enjoyment of the story was because I enjoyed the story, not because it was read aloud.

And lastly an audiobook is not “based on” a book, it is the book, provided it is not an abridged version. It is not a play or an adaptation as it is a word for word reading of the book down to every last “he said”. I find the notion that an audiobook is not a book to some people downright baffling. Given the fact that story telling began as an oral tradition and only later became a written on, to denigrate listening to stories as “not counting” or “not reading” is downright bizarre and quite often smacks of misplaced snobbery.

(And if it makes any difference, I actually I did come within touching distance of the ebook as I used that to check details for my review, and I enjoyed rereading certain passages as I did so.)

LikeLiked by 1 person