I’m working very hard at staying on track with this series of posts. This is part 4 of what should be a 7 part series.

A Family Christmas Part Five: The Christmas Tree

Chapter five of the Christmas book and we finally get to the decorating of the tree. It’s pretty common for people to put their trees up around the beginning of advent, or the 1st of December depending on how advent falls, and many people even have them up through November. So it perhaps seems quaint and old-fashioned (even with a real tree) to wait until a couple of days before Christmas to put up your tree.

The children begin to decorate the tree with items common today – baubles and bells and so on – and some more uncommon things like cotton wool, strips of tinfoil (though angel hair tinsel can be bought most places these days) and real candles. They are safety conscious in not putting cotton wool too near the candles, but a bit rude about artificial coloured lights that some people have. We had coloured lights almost identical to these on our tree when I was a child (but not LEDs!) and every year I think about buying a new set because I was so disappointed when they finally broke and my mum replaced them with boring white lights. (Though I also have boring white lights on my tree as I didn’t see any coloured ones when we were buying the tree).

Anyway, this prompts the children to ask about the first Christmas tree. Mother doesn’t know (of course) but she does know a story about a Christmas tree so she gets a turn to tell a story.

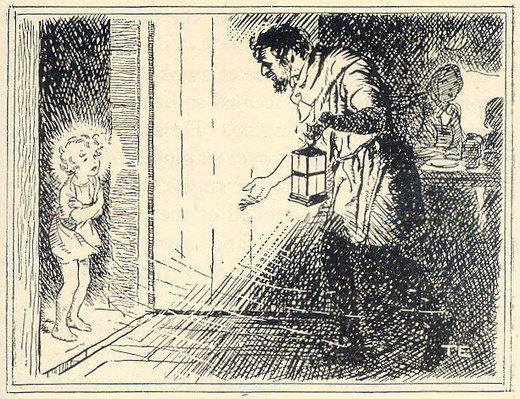

A forester, long ago, takes in a frozen child who appears on their doorstep in the evening. In the morning the child is revealed to be the Christ-Child and he plants a fir branch in the ground, telling the family that it will grow into a tree which will bear fruit every Christmas so that they will always have abundance. Peter points out that fir trees have no fruit, and Susan says it has pine cones.

So I’m not very clear on what that all means. Did the family’s tree produce something other than pine cones – a true miracle? Or just pine cones which, apart from as fuel for a fire, are fairly useless?

I found a couple of other versions of the story – one which ends – The Christ Child went into the front garden of the cottage and broke a branch off a Fir tree and gave it to the family as a present to say thank you for looking after him. So ever since them, people have remembered that night by bringing a Christmas Tree into their homes!”

A bit of a lousy present if you ask me – here’s a branch from your own tree… not even magically planted for you.

But another has He then broke a branch from a small fir tree and planted it, while telling them: “From this day on, this tree shall bear fruit at Christmas and you shall have plenty even in the cold winter.”

As they stood listening, the branch grew into a beautify tree covered with golden apples and silver nuts, and that poor family was in need never again.

Which sounds much better, and perhaps more like what Blyton intended us to understand.

Religious confusion aside, the talk of pine cones allows Blyton to impart some nature-knowledge via the children about different kinds of evergreen trees and the cones that grow on them, and also what uses the wood from the trees has.

Then it’s back to decorating with the star at the top – representing the Star of Bethlehem, and Mother is able to tell the children that Christmas trees have only been in England for around a hundred years – since 1841 when Prince Albert set one up at Windsor.

There are also presents on the tree which Mother points out have to be proper presents, ones for joy, not to be useful. Putting actual wrapped presents on the tree is another old-fashioned idea which I had to explain to Brodie, though I swear that I read about someone doing it recently (I suspect in a fiction book) having kept up that old custom.

The quote at the beginning of this chapter is from Eugene Hamilton.

And now the fir tree…

Acclaimed by eager, blue-eyed girls and boys,

Bursts into tinsel fruit and glittering toys,

And turns into a pyramid of light.

This took some finding as he seems to be known as Eugene Lee-Hamilton (a largely forgotten poet it would seem), but I tracked down this quote as coming from King Christmas, which you can read in full here.

Now for the changes.

The artificial coloured lights referred to above are now electric lights. The other modernisations include removing a couple of lines –

The gong sounded for lunch, and the maid looked in admiration at the tree. What a beauty.

Though this makes Peter talking about what’s for lunch seem a bit of a non sequitur, and

up in the nursery

As perhaps modern children would be confused why they have a nursery for children who are all over the age of 5.

When the children suggest uses for fir tree wood, they originally had three – Masts of ships, telegraph poles and scaffolding poles. Scaffolding poles has been removed, and so mother now says both those things are correct rather than all those things. It’s funny, that while scaffolding poles are definitely not wooden any more, very few trees are cut down to make masts for ships either. (No doubt there will be some, as various historic ships will need maintenance, but it’s not a common use any more).

Dressed (as in the tree was to be dressed the next day is changed to decorated, but the next sentence still reads the tree always looked so pretty when it was dressed in ornaments, and Ann still says Now we’ll dress you.

Gay on one occasion is bright, on the other – the gay candles, it’s just removed.

An interesting paradox appears when mother says the first Christmas trees came to England a hundred and fifty years or so ago, and later puts the date as 1841. Originally it was a hundred years or so ago. 1841 + 100 = 1941, and with The Christmas book being published in 1944, that is very close to 100 years ago. However, 1841+150 = 1991. Even allowing the or so to account for ten or fifteen years, we are still ten years off when this collection was published. Either way, it makes no sense. This is very obviously set much further back – it could perhaps be 1950s or even 60s, but it’s absolutely not the 90s. Even with the little modernisations children of the 90s didn’t talk like that, put real candles on their trees and so on. (Ok, a few very posh boarding school ones might have, but on the whole, no).

The capitalising of holy child, he, and him when talking about the Christ-Child is removed, but he is still The Christ Child Himself. On one occasion Blyton capitalised Tree as in Christmas Tree – the royal one, so perhaps deliberate? but this has been removed. As as the capital S in the Star.

Randomly the bushy top of the tree has become the bush top, and Mother is once referred to as Mum and once as Mummy.

The Tiny Christmas Tree

This was first published in Sunny Stories 256, in 1941, with illustrations by Dorothy M. Wheeler. Apart from this 2015 collection it has only appeared in Tales After Supper with illustrations by Eileen Soper.

This is one of the shorter stories in the collection. There’s a tiny tree on the Christmas tree lot and it is teased by other trees for being so small. After all the bigger trees are bought for houses and schools the tiny one is finally bought by two children. The house it goes to already has a big tree, and the little one finds itself hung with odd things like coconut and seeds as it is to be an outdoor Christmas tree for the birds.

Only a few changes as it’s a short tale –

Coco-nut is now just coconut, which makes sense.

When passers-by admire the tree and say let’s have one ourselves next winter this has been changed to let’s do one ourselves. Why can’t they just have one? Someone will have to do it, maybe them, or perhaps their children/grandchildren/nieces and nephews/neighbour’s children… it doesn’t matter, the point is they like it and want one.

Interestingly the family still have a drawing-room.

A Family Christmas Part Six: A Christmassy Afternoon

There’s a bit of everything in this chapter. Making Christmas cards and crackers, and Mother talking about their history (yay for Mother knowing something else!). Then Father comes home and imparts his knowledge about feasts and mince-pies.

The opening quote is again from Old Christmastide by Walter Scott –

Then the grim boar’s head frowned on high,

Crested with bays and rosemary.

. . . . .

There the huge sirloin reeked hard by,

Plum-porridge stood, and Christmas pie.

Quite a bit is done to try to modernise this chapter. Another reference to a hundred years ago is changed to a hundred and fifty years. Yet Mother still refers to the beginning of the last century. As before, is this 1991, in which case she’s still (correctly) talking about the early 1800s, or is it 2015 and she’s talking (incorrectly) about the early 1900s?

At this point I started thinking about other editions of The Christmas book and upon checking, yes, there’s one published in exactly 1991. (It was split into two, with the family parts in 1991, and the historical/nativity tales in 1993). So it actually makes a lot of sense that various edits were made for the 90s editions and this 2015 book has just lifted that text. Without consulting the 90s editions it’s impossible to say if further changes have been made, but this just highlights the futility of making updates. They go out of date so quickly!

The children’s grandfather’s firm was one of the first to print Christmas cards, this is now your great-grandfather’s firm. Interesting that we’ve added fifty years but only one generation!

The original text is not very clear on the grandfather thing, actually. It’s first as above, the children’s grandfather who had a card printing firm. Mother then says that grandfather gave me when talking about her box of Christmas cards. Initially you’d assume that’s still the children’s grandfather, but she then says your great grandfather when talking about sending some of the cards. It’s very possible that the card-printing firm owner’s father sent Christmas cards, but it somehow makes it less clear. Anyway, the reprint has all references as great-grandfather.

Mother also talks about the differences with crackers when my mother was a child rather than when I was a child.

A reference to the King and what he has on his table at Christmas is changed to the Queen – though of course it’ll need changed back to King now.

Mother’s reference to celluloid cards – “Then we had cards of coloured celluloid,” said Mother. “You can still see them sometimes.” is cut completely, though I can’t see why. If they had to update it, they could easily have changed we to there were, and the second line to you don’t see them now or similar.

Also cut is a reference to in the nursery, while another reference to the the nursery is changed to the living-room.

References to cooks and maids are removed – originally Mother said Cook is out and she left the pudding boiling now she says just I left it boiling.

When talking of mince-pies it originally read “Well, how funny – here comes one for you!” said Mother, as the door opened, and the maid came in carrying a tea-tray. Sure enough, on a dish, were piled the first mince pies. Without the maid it is “Well how funny – because we’re having them for tea!” said Mummy. Sure enough, at tea time on a dish were piled the first mince-pies.

Not the change of Mother to Mummy above, this happens a few times in this chapter, as well as a couple changed to Mum, and one Mother to their Mother.

Three-penny bits (for inside the Christmas pudding) are now just money.

The children no longer print in their cards but write, likewise the printed cards are written. They don’t paste things into their cards but glue them instead.

For some reason the family are no longer allowed to hang their cards in separate areas – originally The mantel-piece was full of cards that had come for the children. Downstairs Mother’s mantel-piece and book-cases were covered in them too. Now The mantel-piece was full of cards that had come for the family.

I’ve gone on for ages it seems, but there’s more! We are into the small and petty now.

Of course gay is changed, this time to pretty.

But nowadays is changed to Nowadays – I’m sure that I did learn at school that you shouldn’t start a sentence with a conjunction (or was it a preposition?) like but or and, though a quick internet search tells me that that’s not really a rule at all. But (see what I did there?) perhaps the 1990s editors had also been taught that.

Mother says that the King always has a baron of beef at Christmas, the new version has her add I’ve heard at the end, so perhaps the Queen (as it is in the new version) doesn’t and this is their way of making it no longer a fact?

Sirloin of mutton is changed to lamb.

Interestingly the story told is that sirloin comes from a king knighting the loin as he liked it so much. This sounded highly improbable and the internet tells me it is actually from French surlonge, literally “upper part of the loin,” from sur “over, above” + longe “loin,” from Old French loigne.

Therefore, Daddy now adds they say before he tells that story, which hints that it may not be true. However, as Peter still says Oh, is that really how the sirloin got its name?, and nobody corrects him, it’s not a very effective way of saying it’s an old wives’ tale

The hogs’ head which was wreathed with bay is now wreathed with bay leaves.

And lastly with is added to this line It was nice sitting there in the nursery, [with] the big fire glowing, and the holly round the walls, its berries shining red.

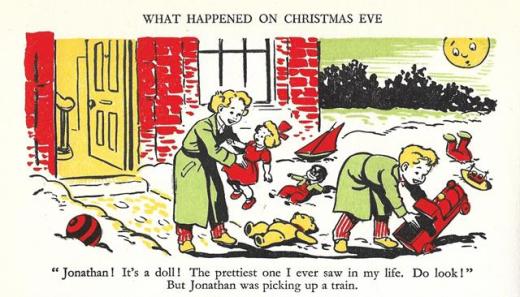

What Happened on Christmas Eve

This was first published in Sunny Stories 419 (1947) with illustrations by Jessie Land. I have it in The Eighth Holiday Book (1953) with illustrations by Robert MacGillivray. It can also be found in Enid Blyton’s Bedtime Stories (1970) and two prints of The Little Brownie House and Other Stories (1993 and 2015).

Santa Claus has another mishap in this tale, it has a few similarities to Santa Claus Gets a Shock.

Santa is out delivering presents, but misses out Jonathan and Elizabeth as they have not been good. Just as he takes off for the next house an aeroplane causes the reindeer to take evasive action and Santa’s sack falls overboard.

Inside, Jonathan and Elizabeth hear and see the toys falling, and go outside. Having gathered them up for Santa, they then see Santa return and he rewards them for their help.

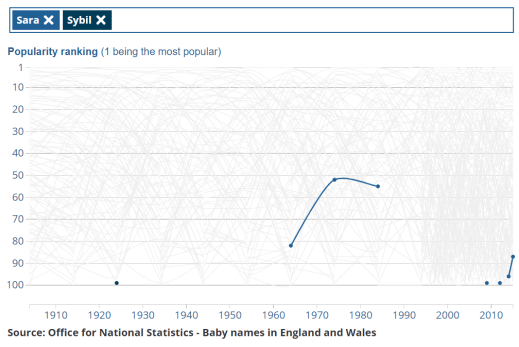

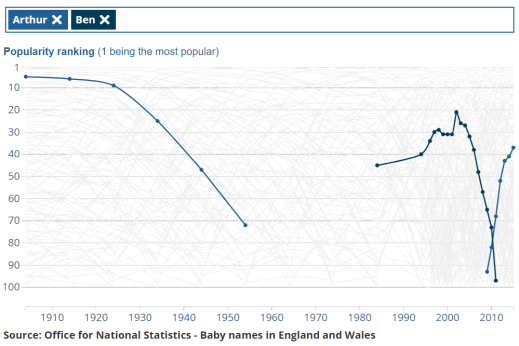

I think this is the first story in the collection to change any names. This is disappointing as they were doing so well! In this Sybil becomes Sara and Arthur becomes Ben (what, there are no modern A names now?).

The only good thing about this is I’ve had an excuse to create more graphs on the popularity of names!

While Sara is definitely more popular than Sybil has ever been (Sybil is that single dot at about 98 or 99th place in about 1924) it’s not a hugely relevant name in 2015.

Similarly, while Arthur did disappear from the top 100 in the late 50s, it has made a huge resurgence since around 2008. Meanwhile Ben peaked in the early 2000s and disappeared ten years later.

Unsurprisingly the golliwogs are changed to teddies as they fall out of the sack. However this means that when they spot three golliwogs/teddies in a row, and then two fat teddies, the two fat teddies have to be changed to two fat toy pandas. It would have been easier to change the golliwogs to pandas, perhaps, rather than making two changes?

The reindeer hoofs are now hooves. While hoofs is still correct it is less common than hooves now.

Weirdly when the toys fall with a Bumpity-bump! Clitter-clat! Rilloby-roll! the last hyphen is removed, but when that sentence is repeated (when we see the children’s POV) it is back.

Mother is no longer capitalised when in dialogue as their mother and your mother.

And lastly, when Blyton speaks to the reader at the end to say we can all tell you that! there has now been a for certain added.

But despite all those changes the new aeroplanes are still just for the boys.

This is wonderful. Thanks so much for all the work you must have put in to writing it. Chris

LikeLike

The things we think of as associated with a traditional Christmas turn out to be fairly recent additions. Some are very recent. Bing Crosby has, obviously, only been popularising the song ‘White Christmas’ in the 1954 American movie of that name since 1954.

But as you point out, the tradition of having a christmas tree was only imported, from Germany, in Victorian times, by Prince Albert. Before that, the tradition was to have a Yule log, which seems to have doubled as a practical way of keeping warm, by burning it on the fire! We still have some faint vestiges of that tradition: you can still find cakes designed to look like a yule log, and it is still a design found on christmas cards.

There’s a traditional German song, ‘Oh Tannenbaum’, which translates into English as ‘Oh Christmas Tree’, which reflects the Germanic origin of the christmas tree. In more recent times, the communists appropriated the tune, for their ‘marching’ song, The Red Flag!

Our christmas traditions really begin with Charles Dickens, in the 1830s, and in particular with his novel ‘A Christmas Carol’, much loved by the Americans. Dickens’ novel seems to be recording traditions which were already associated with christmas, rather than inventing them, but there are few earlier written sources.

Christmas as a name, i.e. christ’s mass, was added to the ancient pagan midwinter festival by the early Christians, in an unsuccessful attempt to hijack that festival. Christ was plainly not born in midwinter: shepherds could not have been raising their flocks of sheep at that time of the year. But our christmas traditions have little to do with religion: Ebeneezer Scrooge and Santa Claus, with reindeer from the north pole, snowdrifts, snowmen, and christmas as a major shopping event, are the real meaning of christmas. For us and for the children depicted in Blyton’s books.

LikeLike

Funny you should mention Yule logs and Yule log-shaped cakes as I’ve already made the same point in post 5, which should be up by the end of the week.

It’s easy to assume that all our traditions have been around forever (though, some of them have, in some form or another seeing as Christians stole many of them from older religions) as if it’s been around all our life, and perhaps our parents’ and grandparents’ lives it can easily feel like it has been that way forever.

LikeLike

Pine cones are edible!

In the period of wartime austerity when the books were written, in the 1940s, Blyton’s readers would have known this. All kinds of unusual foods were eaten in those days, reflecting the lack of what we would think of as more ‘normal’ items, which were either rationed or simply unavailable because of the war.

You can eat the seeds, better known as pine nuts, of certain species of pine growing in a few parts of the world, though not in Britain. I’m talking about pine cones, not spruce or fir cones. But spruce cones are also used as food, and as medicine, and young fir cones are also edible.

The hard, woody pine cones that you find on the ground and use as christmas decorations are not edible, but neither are they poisonous. They’re just too tough to eat. Earlier in the growing season, pine cones are green and solid, not brown and scaly: these immature pine cones are the ones which are edible. They’re very popular with squirrels, which is likely how people came to eat them (if they couldn’t get squirrel!!), by aping the behaviour of the squirrels.

In Russia, tourists bring jars of pine cones home from Siberia as souvenirs, and make jam from them (it’s more like honey than jam, in fact). The cones can be treated in other ways, to extract this honey-like syrup, which is then used in tea for drinking. Very young green cones, diced, can be brewed up directly as tea.

Needles from spruce and pine can be eaten all year round, mainly in recipes for spruce tea or pine needle tea, or as a pine syrup for use as a cocktail mixer, or as a cough medicine.

LikeLike

Ok – I’ll downgrade pinecones from useless to just rather unappetising. My other point still stands, though, that there were already pine trees all around, which would presumably produce pine cones already, so a poor gift unless the miracle was for it to bear something different.

LikeLike