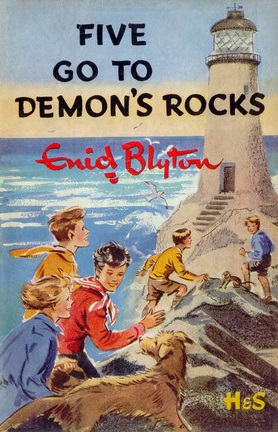

I have now reached book #19 of 21. A lot of Blyton fans seem to feel that the latter books in the series are the weakest. I would certainly say that books 20 and 21 – Five Have a Mystery to Solve and Five Are Together Again – are the weakest of the series, but I don’t think that Demon’s Rocks is weak in any way at all.

In fact it is my sixth favourite Famous Five title, coming in above a lot of the earlier books which many fans would class as the best ones.

It is Demon’s Rocks that has given me a life-long association between Enid Blyton and lighthouses. With that in mind my first post is going to be light on plot and heavy on location.

The location of the lighthouse

I’ll begin this section by sharing that – on paying closer attention to the finer details of this book – I realised that my mental picture of Demon’s Rocks isn’t at all accurate.

In my mind, if you were out to sea, you would look landward and see Demon’s Rocks village on the left with the harbour out front. Then to the right of that the land rising to cliffs, a rocky ‘beach’ in front, running from near the harbour all the way along the cliffs. I therefore pictured the lighthouse sitting on those rocks, close-ish to the cliffs. The boat, in my mind, was needed as parts of the rocks were submerged at high tide, with enough sea between between the rocks and the harbour to necessitate a boat at high tide.

My mental picture also has the front door facing out to sea. This is entirely wrong for a few reasons. Firstly that would mean the waves were directly battering it and the stairs (which is foolish), secondly the dust jacket clearly shows the door on the opposite side to the sea.

Now, the left-to-right layout is never contradicted nor proven in the book, so we can picture it that way or as a mirror image. I suspect the Five heading towards the lighthouse on their right contributes to my left-to-right image, though with the sea behind the lighthouse that doesn’t mean anything. We don’t know if they are coming from their boat here or heading back after exploring.

Anyway – the true layout, now that I have paid attention, is that the lighthouse actually stands on a rocky bit of land out to sea. (I am imaging most of my readers saying ‘well DUH’ at this point.). At low tide enough rock is uncovered to enable people to walk out to the lighthouse.

The car swept down almost to the edge of the sea. The light-house was now plainly to be seen, a good way out from the shore… ‘These are the rocks that we can walk over when the tide’s out,’ said Tinker.

Clearly the young me didn’t pay enough attention to the very clear description here, and the older me also didn’t pay enough attention and just relied on my childish imagination.

I think this time, reading for a review plus having recently read about a similar lighthouse – the Bell Rock Lighthouse, which isn’t all that far from where I live – finally hammered the correct details into my head.

The real Demon’s Rocks?

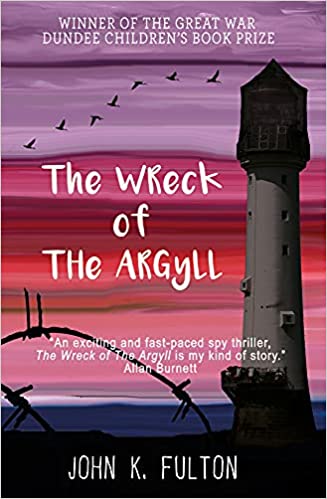

You can’t walk to the Bell Rock Lighthouse though, as it’s several miles off the coast. I still wondered for a brief moment if that one had inspired Blyton. It is, after all, the oldest sea-washed lighthouse still in operation now, and she may well have heard the story of the HMS Argyll running aground on the Bell Rock during WWI.

However, I thought it was possibly more likely that her inspiration had come from closer to home. It’s also entirely possible that she was inspired by something she had read in a book, or in a postcard from abroad. But still, I fell down a several hour-long rabbit-hole on Wikipedia and other sites, looking for sea-washed lighthouses around England that may have been inspiration for Tinker’s lighthouse.

There are a few offshore lighthouses off the coast of England – but the key phrase there is off the coast, anywhere from 1.25-30 or more, so definitely not a walkable distance! Most of them are, like the Bell Rock, well off the coast. There are a couple that are positioned like Demon’s Rocks.

Beachy Head lighthouse (my top contender) is at the rocky base of the cliffs in East Sussex, and is in fact, a replacement for an older lighthouse which had been built up on the cliffs but suffered from its light being obscured by fog. (In Demon’s Rocks it’s the other way around, but this is still a little bit of a parallel that I think lends credence to my theory.)

Here you can see it at high tide – cut off from land, and again at low tide.

Photos by Mike B on Pexels and Jaleel Akbash on Unsplash

You can walk to Beachy Head Lighthouse at the lower end of low tides, across the rocks. It doesn’t look very much like Demon’s Rocks lighthouse, but then Soper’s illustrations aren’t exactly gospel (they even sometimes directly contradict the text). Plus, of the few lighthouses that can be walked to at low tide Beachy Head is one that looks like the traditional image of a lighthouse. The others are very short and squat, or boxes on legs.

New Brighton Lighthouse perhaps looks a little more like Soper’s illustration, and it can be walked to, but the beach surrounding it is sandy and it lacks cliffs.

Photos by David Hughes from Pixabay and Marius Cern on Unsplash

Soper’s illustration probably most resembles lighthouses like Flamborough Head – but without the buildings at its base, Heugh Lighthouse in Hartlepool, Hurst Point in Hampshire or Trevose Head, Cornwall. It’s not unreasonable to suggest, though, that Soper’s inspiration could have come from an entirely different place from Blyton’s, as Blyton doesn’t describe the outside in great detail, other than the balcony and it being tall.

Flamborough Head by James Kemp on Unsplash and Trevose Point by Wirestock on Freepik

‘That one’s made of stone. It’s wave-swept so it has to be fairly tall, or the shining of the lamp would have been hidden by the spray falling on the windows.’ – Jackson, the driver.

As a child (and as an adult even) I didn’t realise that wave-swept (or sea-washed) meant more than it being close enough to the water to be wetted, it actually meant out to sea.

Anne gazed at it. It was sturdily built and seemed very tall to her. Its base was firmly embedded in the rocks below it…. A gallery, rather like a verandah, ran round the top, just below the windows through which the light-house lamp once shone.

Mind you, Soper didn’t draw a very tall lighthouse on the cover. It looks rather squatter than I’d expect given the four floors beneath the lamp room and all the references to it being tall. Then again, any taller and it wouldn’t have fitted on the cover!

Inside the ground floor has the trap-door which will become important in the latter parts of the story. Then there’s a store room, an oil room, a room used as a bedroom and then the sitting room/kitchen and the lamp room at the very top. No mention of a bathroom at all – not even for washing up or brushing teeth!

I had forgotten that there is one of those little bits of tragic history that Blyton likes to throw in behind the lighthouse.

It’s an odd little light-house, really—built by a rich man years and years ago. His daughter was drowned in a ship that was wrecked on these rocks—so he built a light-house, partly as a memorial to the girl, and partly to prevent other ship-wrecks.

The practicalities

I have to say the Five had me quite stressed at times. They rightfully point out that if they leave the boat at the lighthouse they have to be back in time to walk across the rocks before the tide turns.

Nowadays of course you’d just google tide times, but they don’t have that luxury. There may have been a tide times chart up at the harbour – because of course it changes daily – but the Five are never shown to consult such a thing nor mention any specific times.

When they cross rocks by Kirrin Island (to get to the wreck/newly discovered cave) it is very slippery, but they are lucky that the path to the lighthouse aren’t too bad. They are described as wicked rocks – with sharp edges and points that would hole a ship at once.

The lighthouse of old

The chapters where they are trapped in the lighthouse are probably some of my favourite parts of this book, and they give us a glimpse of the lighthouse when it was working.

The bell they find was cast in 1896 – which sounds pretty old to us, but it’s younger than Jeremiah Boogle (my maths on his age will be in the next post). It hadn’t been heard for 40 years, (around 1921) he says, when it suddenly rings out in the middle of a dark and stormy night.

‘A bell! A bell I’ve not heard for nigh on forty years!’ said old Jeremiah, standing up, hardly able to believe his ears. ‘No—it can’t be the light-house bell. That’s been gone for many a day!’

The light also won’t have been seen for forty years so it’s not surprising that Jeremiah Boogle is astounded and wonders if he isn’t imagining it all.

Part two will be all about Jeremiah Boogle and the Wreckers.

It sounds familiar to me. I think I have read it. Thank you 😊

LikeLike

It’s a story that is strong in parts, yet is weak in others. I found it quite fast paced as well. Thanks for the research you have done. I love all the lighthouse pix. I live in Australia, where lighthouses are rare and seeing one is a real treat.

LikeLike

I will send MY long list of Demon’s Rocks bloopers in the comments section of your next epistle, thanks Fiona. Be interesting to see if we agree. This book is not a bad yarn, better than the average FF story.

LikeLiked by 1 person